Time

Module 1 can be done in full within 60 minutes or broken into two 30-minute sessions (with slides 1–9 conducted in a single session and 10–14, case study, and handout conducted in the subsequent session).

Summary

The goal of this module is to provide participants an overview of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States, particularly within marginalized and underserved populations. It highlights how the National HIV/AIDS Strategy and HRSA’s SPNS Program are helping to end HIV/AIDS through the coordinated development and implementation of innovative approaches to HIV care. It also serves as a springboard to help clinics initiate important discussions about how to better engage vulnerable PLWHA within their communities into care.

Materials Needed

- Computer and compatible LCD projector to play the PowerPoint presentation

- Paper and easel(s) for taking notes

- Colorful markers

- Tape for affixing paper to the wall as necessary

- Copies of the Module 1 handout to distribute.

Module 1 features presentation material, group discussions, and a group activity.

The Facilitator or other appointed person should write key thoughts voiced by participants throughout the presentation and subsequent discussions on the paper/easel.

Below are key points for the Facilitator to stress during the presentation and discussion topics to explore with the group.

Slide #1

Slide #2: Addressing the United States Epidemic

Start with a discussion of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS).

The NHAS, launched by the White House in July 2012, is geared to mitigating and ultimately ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States.

This national roadmap is crystallized into three overarching goals:

- Reducing the number of people who become infected with HIV

- Increasing access to care and improving health outcomes for PLWHA

- Reducing HIV-related health disparities

How do you think the National HIV/AIDS Strategy is connected to the work we do at the clinic?

What impact have you noticed so far?

Slide #3: NHAS: More Important than Ever

NHAS is more important than ever in light of how many PLWHA are not receiving HIV/AIDS services.

The CDC estimates that 20 percent of the 1.2 million people estimated to be living with HIV in the United States are not in care.

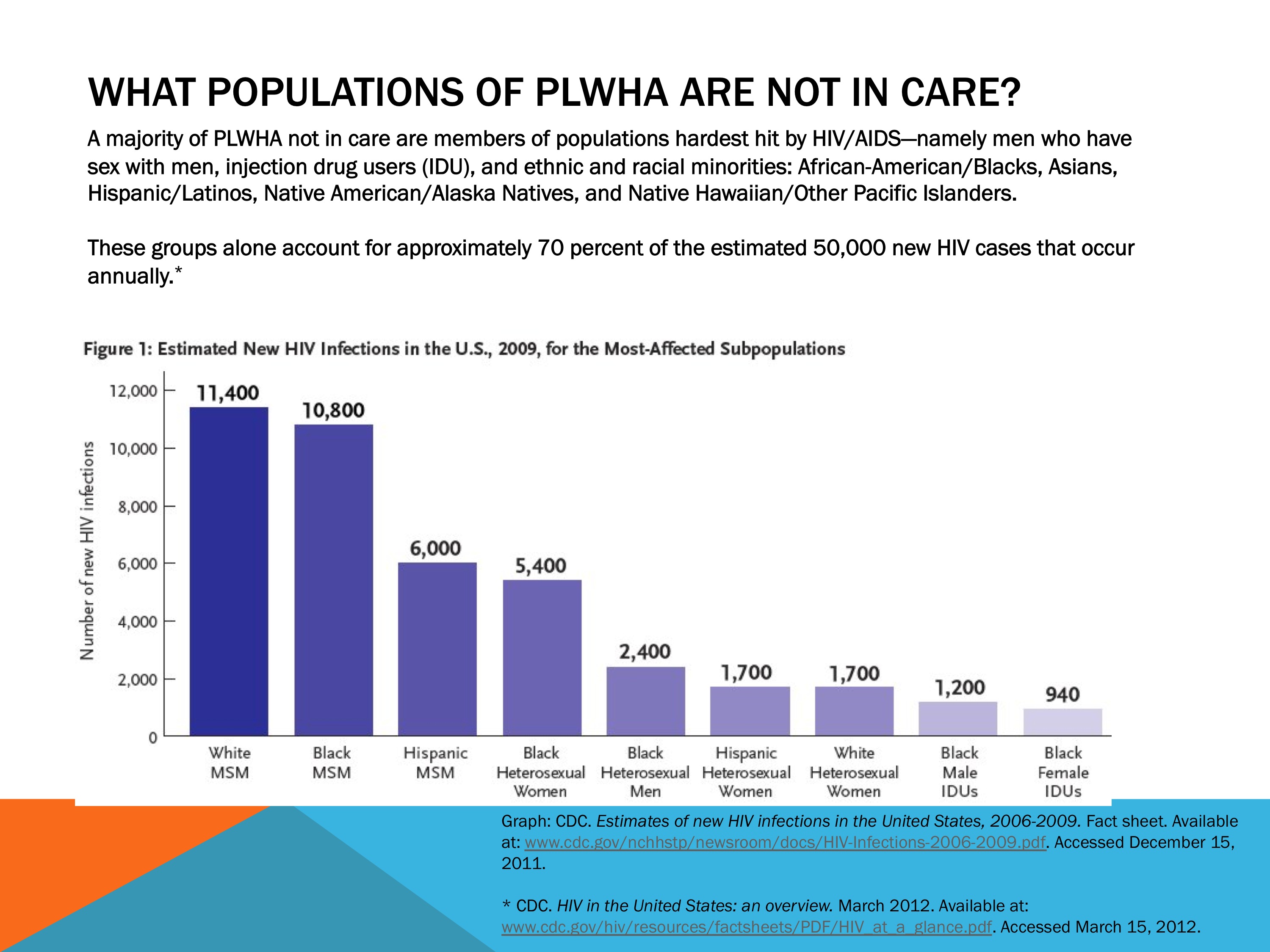

Slide #4: What Populations of PLWHA Are Not in Care?

Marginalized and under-served populations are over-represented among PLWHA in the United States.

Populations that have the least access to care or resources to meet their basic needs bear the greatest burden of HIV.

These groups have been disproportionately impacted by HIV/AIDS since the start of the epidemic in 1981.

Slide #5: Snapshot of the Domestic HIV Epidemic

Here are some statistics that highlight the immense impact of HIV in marginalized communities:

- Though African-Americans represent approximately 14 percent of the United States population, they constitute nearly one half of all PLWHA in the United States.

- Young African-Americans, especially men who have sex with men (MSM), are hardest hit.

- African-American women represent 63 percent of HIV diagnoses among women in the United States.

- In 2010, Hispanics represented only 16 percent of the United States population, but accounted for over 20 percent of new HIV diagnoses and 20 percent of AIDS diagnoses.

- Asians and Native Hawaiians or Other Pacific Islanders (NH/PIs) had the third largest burden of HIV in the United States (after African-Americans and Hispanics) in 2010.

- AIDS rates are 40 percent higher among American Indians/Alaska Natives than Whites.

Slide #6: Other Vulnerable PLWHA Populations Not in Care

Continue the discussion with these statistics:

Other groups that have been disproportionately impacted by HIV nationwide include:

- Sexual minorities, particularly MSM and transgender women

- PLWHA with SUDs

- PLWHA engaged in injection drug use (IDU)

- Women, particularly women of color

- Youth, particularly young MSM of color

- Currently and formerly incarcerated PLWHA

- Vulnerable and highly mobile groups, such as migrant workers, sex workers, and homeless persons

Who are the vulnerable populations served by our clinic?

- What populations of PLWHA within the community does the clinic serve? Who are not served?

- Why do you think some populations of PLWHA are engaged in care at the clinic and others are not? Is it related to the clinic’s operations? To the populations of PLWHA themselves?

- What populations of PLWHA does the clinic wish to target more effectively?

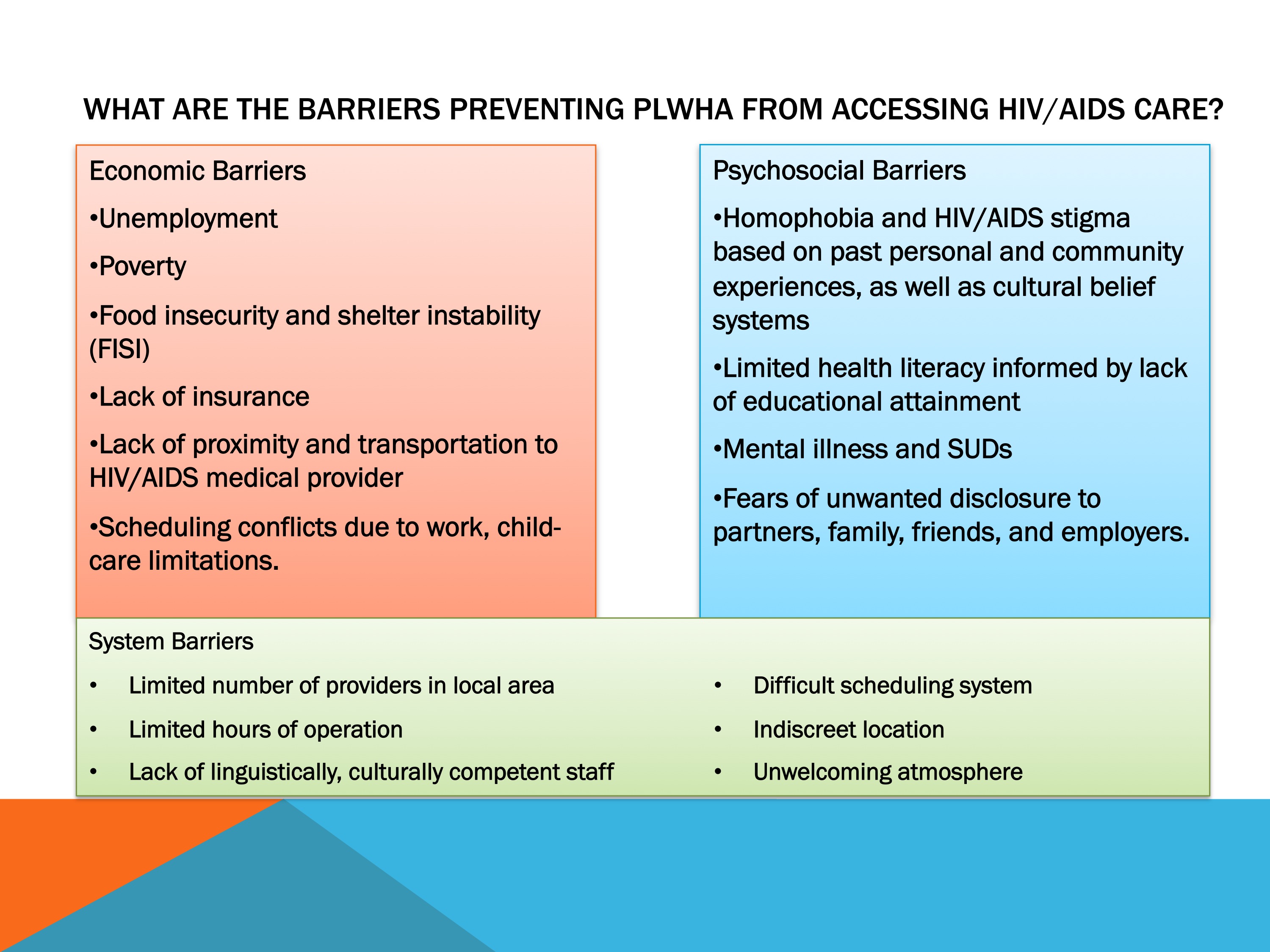

Slide #7: What Are the Barriers Preventing PLWHA from Accessing HIV/AIDS Care?

Here we have a list of economic, psychosocial, and systemic barriers that often prevent PLWHA from accessing care:

- Is there anything listed here as a barrier to care that you find surprising?

- What barriers do you think are missing from each category? Why?

- Have you worked with patients who were reluctant to get tested for HIV due to any of these barriers? If so, which barriers? Are patients testing late for HIV?

- What do you do to help these PLWHA overcome their barriers

to care?

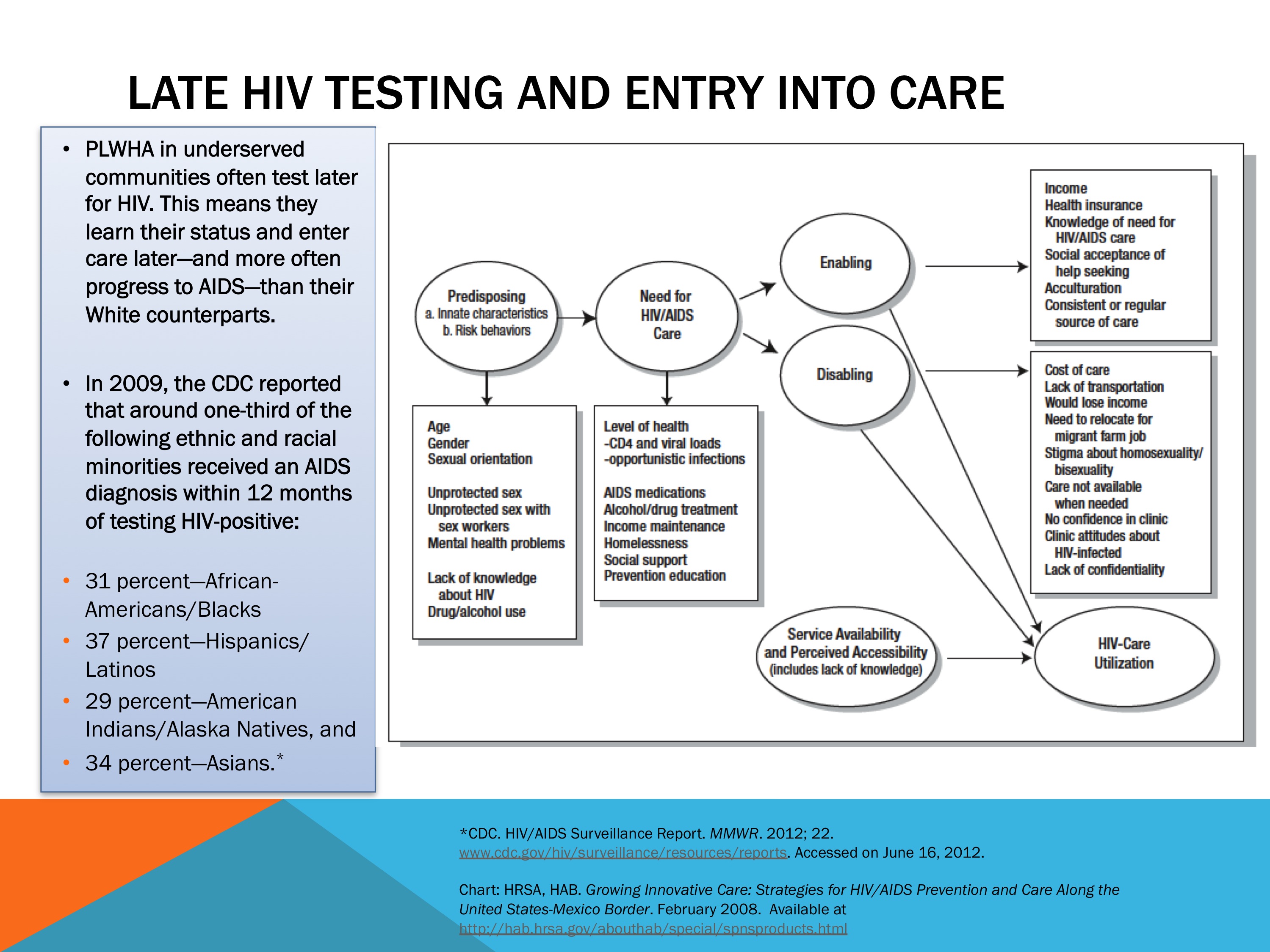

Slide #8: Late HIV Testing and Entry into Care

After the discussion, talk about the health ramifications of late HIV testing.

This diagram serves as an HIV testing logic model, which shows the different issues that often play a role in whether PLWHA access care.

Not accessing HIV care can have serious health implications:

- PLWHA in underserved communities often test later for HIV. This means they learn their HIV status and enter care later—and more often progress to AIDS—than their White counterparts.

- Ethnic and racial minorities have been particularly impacted.

- In 2009, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that around one-third of the following racial and ethnic minorities received an AIDS diagnosis within 12 months of testing HIV-positive:

– 31 percent—African-Americans/Blacks

– 37 percent—Hispanics/Latinos

– 29 percent—American Indians/Alaska Natives, and

– 34 percent—Asians.

Slide #9: Why Is HIV/AIDS Care Important?

Without intervention, PLWHA most likely will progress to AIDS, undermining their health outcomes, quality of life, and life expectancy.

Research has consistently shown that PLWHA engaged in a holistic spectrum of care are more motivated to:

- Keep appointments.

- Initiate and adhere to antiretroviral therapy (ART).

- Regularly get required lab work.

- Participate in support services, such as mental health, SUDs, alcohol counseling, and dental care.

- Leverage (along with their families) ancillary/wraparound services, such as transportation, food and clothing banks, and health education classes.

- Access ART and support to ensure treatment adherence.

- Replace high-risk behaviors with a healthier lifestyle.

All of these help PLWHA avoid reinfection with HIV; transmission of the virus to others; and exposure to HIV coinfections, such as viral hepatitis, tuberculosis, and other sexually transmitted diseases.

Slide #10: Module 1 Activity: HIV/AIDS Care Case

Study of Bob S.

Bob S. is a 35-year-old African-American male from Baton Rouge, LA. He works as a bartender and has engaged in sex work on and off since his late teens to make ends meet.

He knows HIV is an issue for the African-American community but never thought he was personally at risk for HIV, so he has never been tested.

He also works a lot and, most importantly, fears that family members might see him enter the clinic. He fears being outed as being gay and is worried about HIV stigma.

Bob finally decides to come in for testing after hearing from friends that his former boyfriend is HIV-positive and never told him.

Bob also has been extremely ill on and off for the past 6 months.

Testing reveals that Bob S. is HIV-positive with a CD4 count just under 100.

Be sure to encourage participants not to use real names or any other

identifying information.

- What would you do to help Bob S. deal with this new diagnosis?

- How would you get him into care as soon as possible?

- What are your experiences working with PLWHA testing late for HIV?

- What kept them from getting tested and into care?

- What steps would you take to help Bob address stigma?

- What actions would you take to notify any partners of Bob’s to get

tested while keeping Bob’s identity safe?

Slide #11: HIV/AIDS Care Saves Lives

Look at this incredible statistic:

- Attending all medical appointments during the first year of HIV care doubled survival rates for years afterward, regardless of baseline CD4 cell count or use of ART.

- PLWHA in care also avoid high-risk behaviors.

What other benefits—social, economic, familial, or health-related—have you seen among PLWHA linked to care?

Slide #12: HIV/AIDS Care Is Cost-Effective

Early HIV intervention and treatment is significantly cheaper—sometimes by more than 50 percent—than that associated with late HIV infection and end-of-life care.

Slide #13: Implementing the NHAS, Helping PLWHA Access Care

The NHAS has called on clinics and agencies delivering HIV/ AIDS care and services to find and implement innovative, cost-effective ways to improve their reach and access to PLWHA.

The models of care that we will be reviewing should satisfy this goal and help align clinic activities with the goals of the NHAS.

The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, administered by HRSA, has helped vulnerable PLWHA access care for over 20 years. The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program currently delivers care to over one-half of all PLWHA in the United States.

Through the SPNS Program, Ryan White has supported the development of numerous innovative models to engage hard-to-reach PLWHA into care.

Slide #14: Integrating HIV Innovative Practices

HRSA has launched the IHIP to help health-care providers and others delivering HIV care in communities heavily impacted by HIV/AIDS with the adoption of SPNS models of care into their practices.

This is ultimately about building our knowledge, skills, and abilities to recruit, engage, and retain vulnerable PLWHA into care.

Save the notes from Module 1 for reference during future modules.

Distribute the Additional Engagement in HIV Care Resources Handout.

Additional Engagement in HIV Care Resources Handout: This handout provides information about additional resources related to the SPNS Program, marginalized and underserved PWLHA, and the theoretical foundations and practical application of the models of care discussed in this curriculum.

Additional Engagement in HIV Care Resources:

IHIP Materials

- Innovative Approaches to Engaging Hard-to-Reach Populations Living with HIV/AIDS into Care training manual and webinars available at Integrating HIV Innovative Practices (IHIP).

- Integration of Buprenorphine into HIV Primary Care Settings training manual, curriculum, and webinars available at Integrating HIV Innovative Practices (IHIP).

SPNS Resources

- Download fact sheets about the Special Projects of National Significance: http://hab.hrsa.gov/abouthab/aboutprogram.html.

- Learn more about the following SPNS Initiatives that informed this curriculum at http://hab.hrsa.gov/abouthab/partfspns.html.

American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) Initiative

- AI/AN Initiative Highlights Challenge of Unique Service Settings. What’s Going on @ SPNS. May 2005.

Outreach, Care, and Prevention to Engage HIV Seropositive Young MSM of Color Initiative

- Breaking Barriers, Getting YMSM of Color into Care: Accomplishments of the SPNS Initiative. What’s Going on @ SPNS. December 2011.

- Special Edition of AIDS Patient Care and STDs featuring research about the Young Men of Color Who Have Sex with Men (YCMSM) Initiative.

- Costs and Factors Associated with Turnover among Peer and Outreach Workers within the Young Men of Color Who Have Sex with Men SPNS Initiative. March 2010.

- Magnus M, Jones K, Phillips G, et al. for the YMSM of Color Special Projects of National Significance Initiative Study Group. Characteristics associated with retention among African American and Hispanic/Latino adolescent HIV-positive men: results from the Outreach, Care, and Prevention to Engage HIV-Seropositive Young MSM of Color Special Project of National Significance Initiative. JAIDS. 2009;53(4):529–36.

- Username—Outreach Worker. What’s Going on @ SPNS. August 2006.

- Stigma and the SPNS YMSM of Color Initiative. What’s Going on @ SPNS. February 2006.

- Hightow L, Leone P, Macdonald P, et al. Men who have sex with men and women: a unique risk group for HIV transmission on North Carolina College campuses. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33(10):585–93.

Targeted Peer Support Model Development for Caribbeans Living with HIV/AIDS Demonstration Project

Demonstration and Evaluation Models That Advance HIV Service Innovation Along the United States–Mexico Border

- Special edition of Journal of HIV/AIDS and Social Services featuring research about this initiative. October 8, 2008.

- Growing Innovative Care: Strategies for HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care Along the United States-Mexico Border. February 2008.

- Innovations Along the United States-Mexico Border: Models that Advance HIV Care. 2005.

Targeted HIV Outreach and Intervention Model Development and Evaluation for Underserved HIV-Positive Populations Not in Care

- Special edition of AIDS Patient Care and STDs featuring research about this initiative. June 2007.

- Myers J, Shade S, Rose C, et al. Interventions delivered in clinical settings are effective in reducing risk of HIV transmission among people living with HIV: results from the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Special Projects of National Significance Initiative. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(3):483–92.

Prevention with HIV-Infected Persons Seen in Primary Care Settings Initiative

- Special edition of AIDS Behavior featuring research about this initiative. September 2007;11(Suppl 5).

- Peers Can Play a Vital Role in Prevention with Positives. What’s Going on @ SPNS. January 2007.

- Prevention with Positives Is Off to a Positive Start. What’s Going on @ SPNS. January 2005.

Enhancing Linkages to Primary Care and Services in Jail Settings

- Enhancing Linkages: Opening Doors for Jail Inmates. What’s Going on @ SPNS. May 2008.

- Jail: Time for Testing—Institute a Jail-Based HIV Testing Program. A Handbook and Guide to Assist. 2010.

- Opening Doors: The HRSA/CDC Corrections Demonstration Project for People Living with HIV/AIDS. December 2007.

- Enhancing Linkages to HIV Primary Care in Jail Settings. 2006.

- Special Edition of AIDS Care featuring research about the Enhancing Linkages to HIV Primary Care and Services in Jail Settings Initiative. Summer 2012.

Enhancing Access for Women of Color Initiative

- Lounsbury D, Palma A, and Vega V. Simulating the dynamics of engagement and retention to care: a modeling tool for SPNS site intervention planning and evaluation. Presented by HRSA SPNS Multi-Site Evaluation Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine on May 4, 2012, during SPNS Women of Color Initiative Grantee Meeting May 4–5, 2012.

- Common Voices: SPNS Women of Color Initiative. What’s Going on @ SPNS. April 2011.

Other SPNS Resources

- Improving linkages and access to care. What’s Going on @ SPNS. January 2012.

- The Costs and Effects of Outreach Strategies That Engage and Retain People with HIV/AIDS in Primary Care. March 2010.

Other HRSA, HAB Resources

- Test and Treat. HRSA CAREAction. January 2012.

- Social Media and HIV. HRSA CAREAction. June 2011.

- CONNECTIONS That Count. HRSA CAREAction. February 2010.

- Rules of Engagement in HIV/AIDS Care. HRSA CAREAction. September 2007.

- Outreach: Engaging People in Care. 2005.

- HIV/AIDS in Rural Areas: Lessons for Successful Service Delivery. 2002.

Other Engagement Resources

- Diffusion of Evidence-Based Interventions (DEBIs).

- Antiretroviral Treatment and Access to Services (ARTAS) Implementation Manual. 2009

- Making the Connection: Promoting Engagement and Retention Into HIV Medical Care Among Hard to Reach Populations.

- Connecting to Care: Addressing the Unmet Need in HIV (II).

- CDC. Using Viral Load to Monitor HIV Burden and Treatment Outcomes in the United States.

- Miller W and Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. 2012.

- Naar-King S and Suarez M. Motivational Interviewing with Adolescents and Young Adults. 2011.

- Rollnick S, Miller W, and Butler C. 2011. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior.

- HIV.gov’s Guide to Using New Media Tools in Response to HIV/AIDS. 2010.

- Connecting to Care: Addressing Unmet Need in HIV. 2010.

- Rosengren D. Building Motivational Interviewing Skills: A Practitioner Workbook. 2009.

- National Quality Center. Strategies for Implementing Your HIV Quality Improvement Activities. 2009.

- New York Academy of Medicine. Breaking Barriers: A Toolkit for Getting and Keeping People in HIV Care. January 2007.

Other Journal Articles

- Thompson M, Mugavero M, Amico K, et al. Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: Evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care Panel. Ann Intern Med. June 5, 2012;156(11):817–33.

- Dutcher M, Phicil S, Goldenkranz S, et al. ‘‘Positive Examples’’: A bottom-up approach to identifying best practices in HIV care and treatment based on the experiences of peer educators. AIDS Patient Care and STDs.

- 2011;25(7):403–11.

- Outlaw A, Naar-King S, Green-Jones M, et al. Brief report: predictors of optimal HIV appointment adherence in minority youth: a prospective study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010 Oct;35(9):1011–5. Epub 2010 Feb 8.

- Rajabiun S, Rumptz M, Felizzola J, et al. The impact of acculturation on Latinos’ perceived barriers to HIV primary care. Ethnicity and Disease. 2008;18(4):403–8.

- Drainoni M, Rajabiun S, Rumptz M, et al. Health literacy of HIV-infected individuals enrolled in an outreach intervention: results of a cross-site analysis. Journal of Health Communication. 2008;13(3):287–302.

- Iverson E, Balasuriya D, García G, et al. The Challenges of Assessing Fidelity to Physician-Driven HIV Prevention Interventions: Lessons Learned Implementing Partnership for Health in a Los Angeles HIV Clinic. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(6):978–88.

- Grodensky C, Golin C, Boland M, et al. Translating concern into action: HIV care providers’ views on counseling patients about HIV prevention in the clinical setting. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(3):404–11.

- Thomas L, Clarke T, and Kroliczak A. Implementation of peer support demonstration project for HIV+ Caribbean Immigrants: a descriptive paper. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies. 2008:6(4):526–44.

- Rodriguez AE, Metsch LR, Saint-Jean G, et al. Differences in HIV-related hospitalization trends between Haitian-Born Blacks and US-Born Blacks. JAIDS. 2007;45(5):529–534.

- Sacajiu G, Fox A, Ramos M, et al. The evolution of HIV illness representation among marginally housed persons. AIDS Care. 2007:19(4):539–545.

- Coleman S, Boehmer U, Kanaya F, et al. Retention challenges for a community-based HIV primary care clinic and implications for intervention. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007;21(9):691–701.

- Kinsler J, Wong M, Sayles J, et al. The effect of perceived stigma from a health care provider on access to care among a low-income HIV-positive population. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007;21(8):584–92.

- Tobias C, Cunningham W, Cabral H, et al. Living with HIV but without medical care: barriers to engagement. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007;21(6):426–34.

- Andersen M, Hockman E, Smereck G, et al. Retaining women in HIV medical care. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2007;18(3):33–41.

- Naar-King S, Green M, Wright K, et al. Ancillary services and retention of youth in HIV care. AIDS Care. 2007;19(2):248–51.

- Cunningham W, Sohler N, Tobias C, et al. Health services utilization for people with HIV infection–comparison of a population targeted for outreach with the United States population in care. Medical Care. 2006;44(11):1038–47.

- Steward W, Koester K, Myers J, et al. Provider fatalism reduces the likelihood of HIV-prevention counseling in primary care settings. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;11(1):3–12.

- Fields S, Wharton M, Marrero A, et al. Internet chat rooms: connecting with a new generation of young men of color at risk for HIV who have sex with other men. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2006;17(6):53–60.

- Cunningham C, Sohler NL, McCoy K, et al. Health care access and utilization patterns in unstably housed HIV-infected individuals in New York City. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2005;19(10):690–95.

- Mallinson R, Relf M, Dekker D, et al. Maintaining normalcy: a grounded theory of engaging in HIV-oriented primary medical care. Advances in Nursing Science. 2005;28(3):265–77.

- Needle R, Burrows D, Friedman S, et al. Effectiveness of community-based outreach in preventing HIV/AIDS among injection drug users. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2005;16(1):45–47.

- Myers J, Steward W, Charlebois E, et al. Written clinic procedures enhance delivery of HIV “prevention with positives” counseling in primary health care settings. JAIDS. 2004;37(Supplement 2):S95–S100.

- Morin S, Koester K, Steward W, et al. Missed opportunities: prevention with HIV-infected patients in clinical care settings. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes.2004;36(4):960–966.

- Marseille E, Shade S, Myers J, et al. The cost-effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions for HIV-infected patients seen in clinical settings. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. March 2001;56(3):e87–e94.