35 minutes

PLAN module

Summary

This module provides an overview to foster discussion about the motivational interviewing model of care. Participants will discuss the pros and cons of this module in targeting the marginalized and underserved PLWHA they wish to serve.

Materials Needed

- Computer and compatible LCD projector to play the PowerPoint presentation

- Notes created during previous modules

- Paper and easel(s)

- Colorful markers

- Tape for affixing paper to the wall as necessary

- A bowl or hat for the group activity

- A print-out of the Module 5 Motivational Interviewing Role Playing Scenarios cut into individual strips and folded for selection from bowl

- Copies of the Module 5 handouts to distribute

- Invited guest speaker(s), as needed.

Module 5 features teaching material, guided group discussion, and a group activity.

The Facilitator or other appointed person should write key thoughts voiced by participants throughout the presentation and subsequent discussions on the paper/easel.

Before beginning the presentation, distribute the Module 5 handouts:Sample Motivational Interviewing Session Script and Motivational Interviewing Logic Model.

The Facilitator should introduce the first slide, which serves as a refresher about the last session. It may be helpful to have notes from the previous module up for display to foster discussion.

Slide #41: Training Refresher

Before we begin, let’s review the pros and cons of the previous model we reviewed.

Today’s model of care involves motivational interviewing, or MI. Can anyone describe what MI is to the group? How does it help PLWHA?

Slide #42: Motivational Interviewing

MI is grounded in the transtheoretical model (TTM) of change and can help explain a person’s success or failure in making a proposed behavior change.

In practice, it involves culturally and linguistically competent counseling geared to creating a welcoming environment for PLWHA and encouraging them to get tested and engage in care.

Though time-limited, MI is not a singular encounter, but part of an ongoing relationship that helps PLWHA identify their health goals and develop relationships with clinicians and staff.

It is often followed up with intensive case engagement, including referrals to support and ancillary services, as well as access to incentives or contingencies, such as cash benefits and clothing.

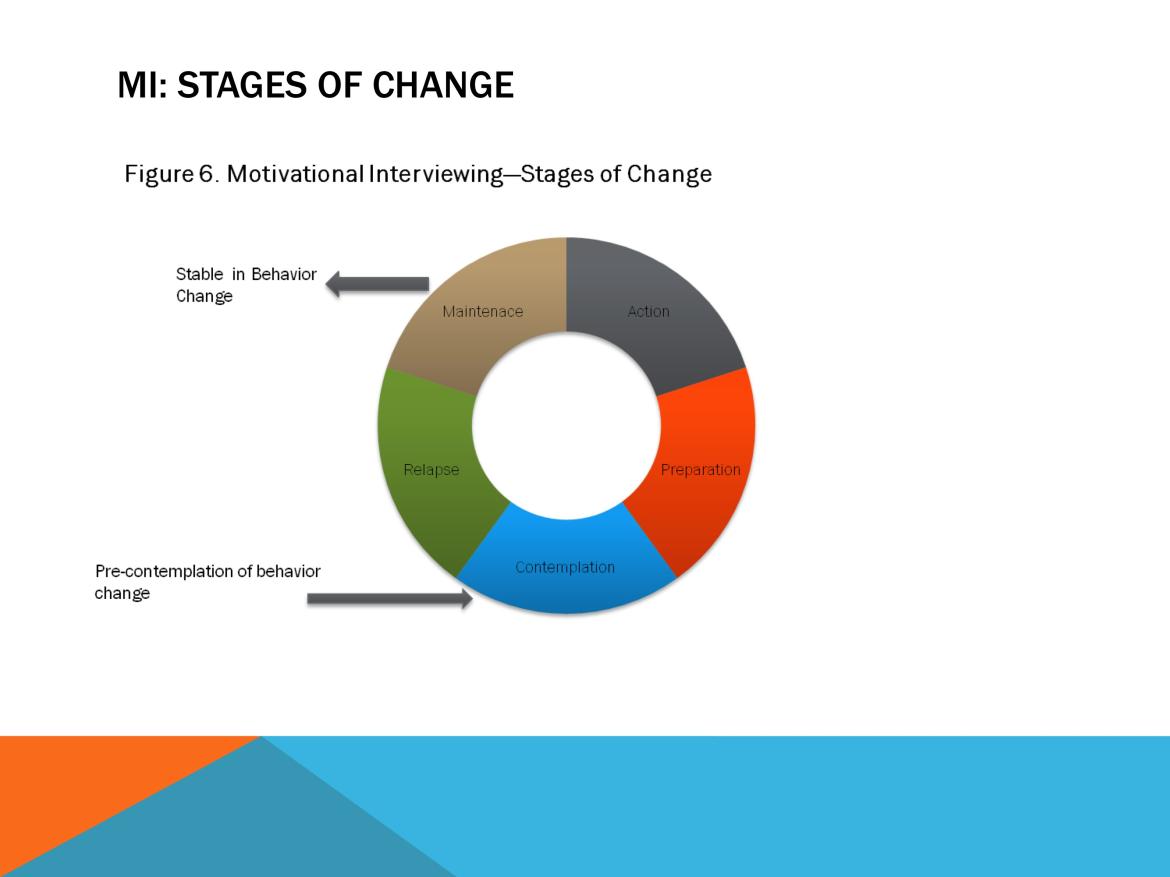

Slide #43: MI: Stages of Change

MI is like the continuum of care—it is not static, but an iterative process, in which MI counselors help PLWHA change their current patterns of behavior in a manner that helps them become engaged and retained in care.

The stages of MI involve:

- Precontemplation: This stage occurs at the start of the conversation, when most PLWHA have not yet acknowledged that there is a problem behavior that needs to be changed.

- Contemplation: At this point in the conversation, the MI counselor has helped the person acknowledge there is a problem, even if he/she may not be ready or even want to make a change.

- Preparation/Determination: Here, the MI counselor helps the patient get ready to change.

- Action/Willpower: The MI counselor empowers patients to outline and start engaging in behavioral change.

- Maintenance or Relapse: MI counselors check in periodically with PLWHA to see if they have maintained their behavior change and are still in care.

Those who make a change and then relapse—fall out of care and/or returned to past high-risk behaviors—can repeat the MI process, perhaps with intensive case management or HSN support.

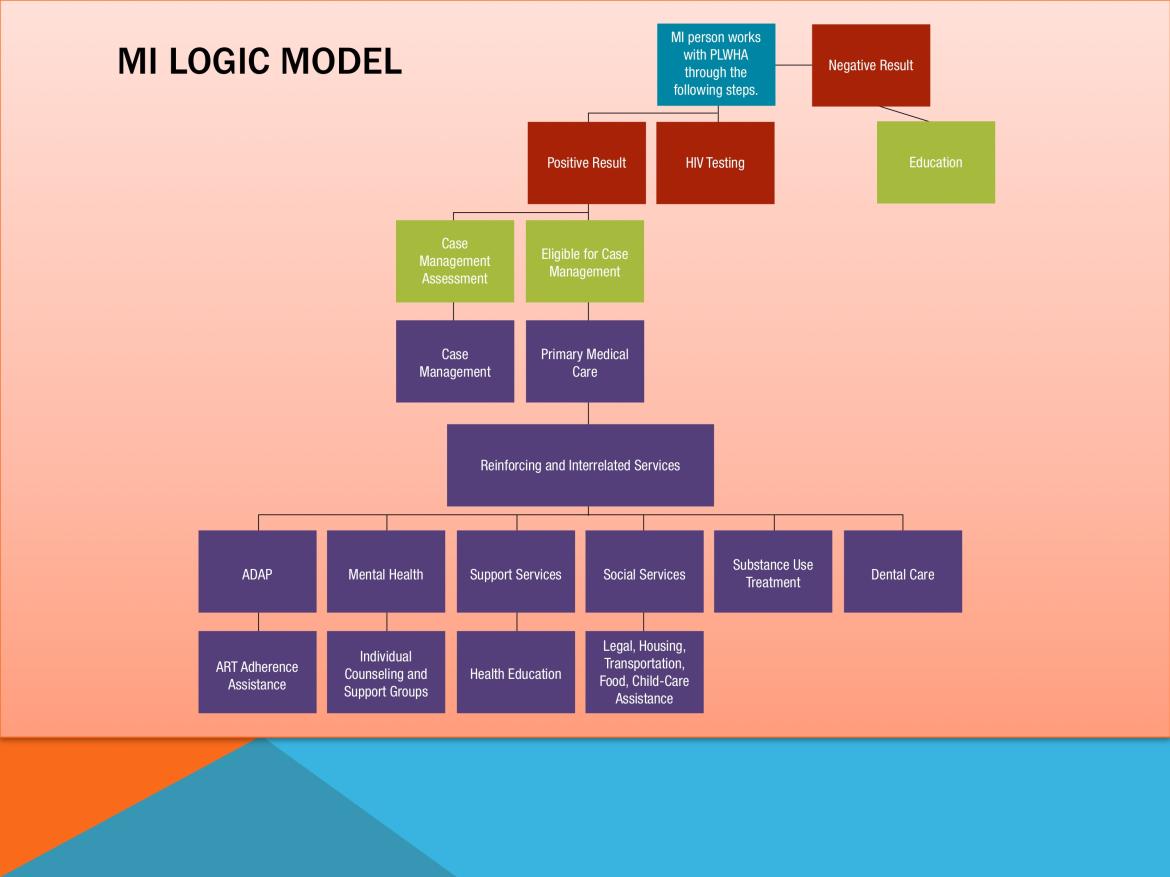

Slide #44: MI Logic Model

Here we have the MI logic model.

We follow a patient from initial encounter to engagement in care.

Slide #45: MI Logic Model, Continued

This model is similar to the traditional street/social outreach

approach; however, in MI, staff engage in an extensive dialog

with PLWHA.

Some issues to consider with this model:

- Staffing/Venue: MI counselors are required to undergo special training to conduct these sessions. They tend to be entry- and mid-level staff and may serve as peers and near-peers to clients.

- Possible Limitations: MI training can be expensive and time-consuming, particularly for agencies that have high turnover rates.

- Tell participants they can learn more at the Motivational Interviewing Web site. It is listed on the Additional Engagement in HIV Care Resources Handout from Module 1.

- MI’s Impact: This model may be particularly successful in reaching younger PLWHA in need of support to engage in testing and care. (Its success also may reflect, in part, the model’s use more often with younger rather than older PLWHA.)

- Unexpected MI Benefits: SPNS participants report that PLWHA who engaged in care following MI often referred their peers to the same clinic—an unexpected, though welcome, spillover effect.

Slide #46: Module 5 Activity: MI Role Playing

The individual scenarios below should be copied, cut out, and folded for selection from a bowl or hat.

Everyone is going to select a scenario from the bowl.

Using the tenets covered in this training session and in the handouts, act out the scenario you selected.

Motivational Interviewing Role-Playing Scenarios

- The Counselor is speaking to Macy, a 25-year-old African-American woman who has two children under the age of 4. She recently tested positive for HIV, but did not fill her ART prescription. She says taking medications would be difficult, since she does not like pills and often feels overwhelmed by work and family responsibilities.

- The Counselor meets with John, a 45-year-old Hispanic/Latino man who moved to New York from Puerto Rico last year. Though he has known he is HIV-positive for 5 years and would like to be treatment-compliant, his IDU and unstable housing situation get in the way.

- The Counselor meets with Kayla, a 30-year-old Asian-American woman living with HIV, hepatitis B, tuberculosis, and several sexually transmitted diseases. She is unmarried and lives at home. She is wary of starting treatment due to fears her family might learn about her serostatus. Her job as a registered nurse also makes her wary of taking any medications that might interfere with her job performance.

- Michael is a 21-year-old African-American gay man in a small city. Though diagnosed with both HIV and AIDS, he does not want to take HIV medications. He says he feels fine. Currently, he resides with an older boyfriend.

- Brenda is 42-year-old Native American transwoman originally from the Lakota reservation. She maintains her appearance through hormone injections, and believes she may have contracted HIV through needle-sharing about a decade ago. She was fully engaged in HIV treatment and care until 2 years earlier, when she met her current boyfriend. Brenda says he is violent. Fearing for her safety, she stopped taking her medications to prevent her boyfriend from finding out she is HIV-positive.

- What they learned from the activity overall.

- If they believe this type of interaction would help PLWHA become better engaged in HIV care at the clinic.

- Whether the clinic could help the PLWHA populations referenced in these examples.

Lead the group evaluation discussion on whether this model of care will work for the clinic. Have participants refer to the Model of Care Evaluation Handout from Module 3.

Tape several pieces of paper with the model of care’s title on each.

Slide #47: Group Module Evaluation

Read each question/statement and write down everyone’s thoughts, questions, suggestions, etc. on the paper.

- Can this model of care be readily integrated within the clinic’s current operations and help it reach targeted populations of PLWHA?

- Does the clinic already use this model of care, perhaps in a slightly different form?

- Can the clinic satisfy all the requirements for this model of care?

- What funding streams, staffing, materials, and other resources are necessary to implement this model of care? Does the clinic have access to these? If not, how will it access them?

- How will buy-in be secured within the clinic?

- Will the implemented model of care be promoted to potential patients? If so, how? Online through social networks? Word of mouth?

- Does this model of care help the clinic identify and engage targeted PLWHA populations into care?

- Compare the pros and cons of this initiative with those of the modules.

If more than 10 people are present, the Facilitator may split participants into two or three groups to discuss the questions above and write their thoughts on the paper. After a few minutes, the Facilitator should reconvene participants. Representatives from each group will explain their colleagues’ thoughts.

Save the paper from this and previous modules for reference in future sessions.

SAMPLE MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING SESSION SCRIPT HANDOUT

Ensure that the Readiness Ruler is administered just before the session, ideally by someone other than you.

Opening Statement

- I’m not here to preach to you or tell you what you “should” do; how would I know, it’s your life and not mine! I believe people know what’s best for them.

- I don’t have an agenda, just a goal: to see if there is anything about the way you take care of your health that you would like to change, and if so, to see if I can help you get there.

- How does that sound to you?

The Session

Begin with a general question regarding their health and health-related behavior. For example, “I’m curious—how happy are you with how well you take care of your health?”

- Follow up by using all your best MI skills: reflections, open-ended questions, affirmations, and eliciting change talk (e.g., “You said you feel you could be doing better. In what way?”). The overall goal here is to communicate a genuine desire to understand, not a desire to push them into anything.

- Try to stay focused on health-related behavior. This part should take 5–10 minutes, but could be more or less depending on the client.

Next, mention that you have some information to share, if it’s OK with them. “I’ve got some information here that’s related to you and your health. Is it OK with you if we go over this a minute?”

- Remember the keys to good feedback: Be completely objective (you are providing them with information that they can take or leave, you are NOT evaluating them). Never argue, and ask a simple question: “What do you make of all this?”

- Follow up with reflections, etc. Be sure to use the Pros and Cons exercise and at least one other strategy to elicit change talk, usually the Readiness Ruler (“On a 0–10 scale, if 0 is not in the least bit ready to see the doctor at least once every 3 months and 10 is as fired up as you can be, where are you?) Remember with the Readiness Ruler to ask, “Why a 3 and not a 0?” if they give you a low number, and “Why such a high number?” if they give a high number (7 or higher).

- Remember, never argue, never push, just be curious and accepting. There’s no hurry. Remember also, the goal here is to maximize change talk by using questions that elicit change talk, by asking for explanation (if they give a little, ask for more details), and by using exercises like Pros and Cons or the Readiness Ruler.

When there are 5–10 minutes left in your session (or when you feel like you’re not going to get any further with Phase I), move into Phase II.

- Do a good summary of everything that’s been said so far. “Let me see if I understand where you’re at with your health right now. . . .” Summarize the things they feel good about and the positive health behaviors you have noticed, starting with general health stuff and ending with specific stuff about their attending doctor’s appointments. Next, move into the things that concern them in general, and things that concern them about appointments in particular. Note, if there is one, the disparity between recommended number of appointments and the number they kept last year. Ask if your summary is about right. If not, correct it.

Ensure that the Readiness Ruler is administered after the session, ideally by someone other than you.