“I went to jail and was in prison. When I was released, my provider gave me transitional housing and later helped me find a house.”

— SPNS patient testimonial

As noted previously, this manual provides insight into the outreach and engagement best practices developed across different SPNS initiatives, most notably:

- American Indian/Alaska Native Initiative

- Outreach, Care, and Prevention to Engage HIV Seropositive Young MSM of Color

- Targeted Peer Support Model Development for Caribbeans Living with HIV/AIDS Demonstration Project

- Demonstration and Evaluation Models that Advance HIV Service Innovation Along the United States-Mexico Border

- Targeted HIV Outreach and Intervention Model Development and Evaluation for Underserved HIV-Positive Populations Not in Care

- Enhancing Linkages to Primary Care and Services in Jail Settings

- Enhancing Access for Women of Color Initiative.

These SPNS initiatives resulted in innovative methods to engage hard-to-reach populations into care. Highlights of approaches common to the SPNS initiatives are provided herein rather than specific detail for each initiative. Information was gleaned from interviews with, and research by, SPNS grantees and evaluators from the SPNS projects and HRSA staff. Several of these SPNS initiatives, in turn, were inspired by the CDC’s Antiretroviral Treatment and Access to Services (ARTAS) approach, which heavily emphasizes linkage to care following HIV testing, to ramp up outreach efforts.16,45-47

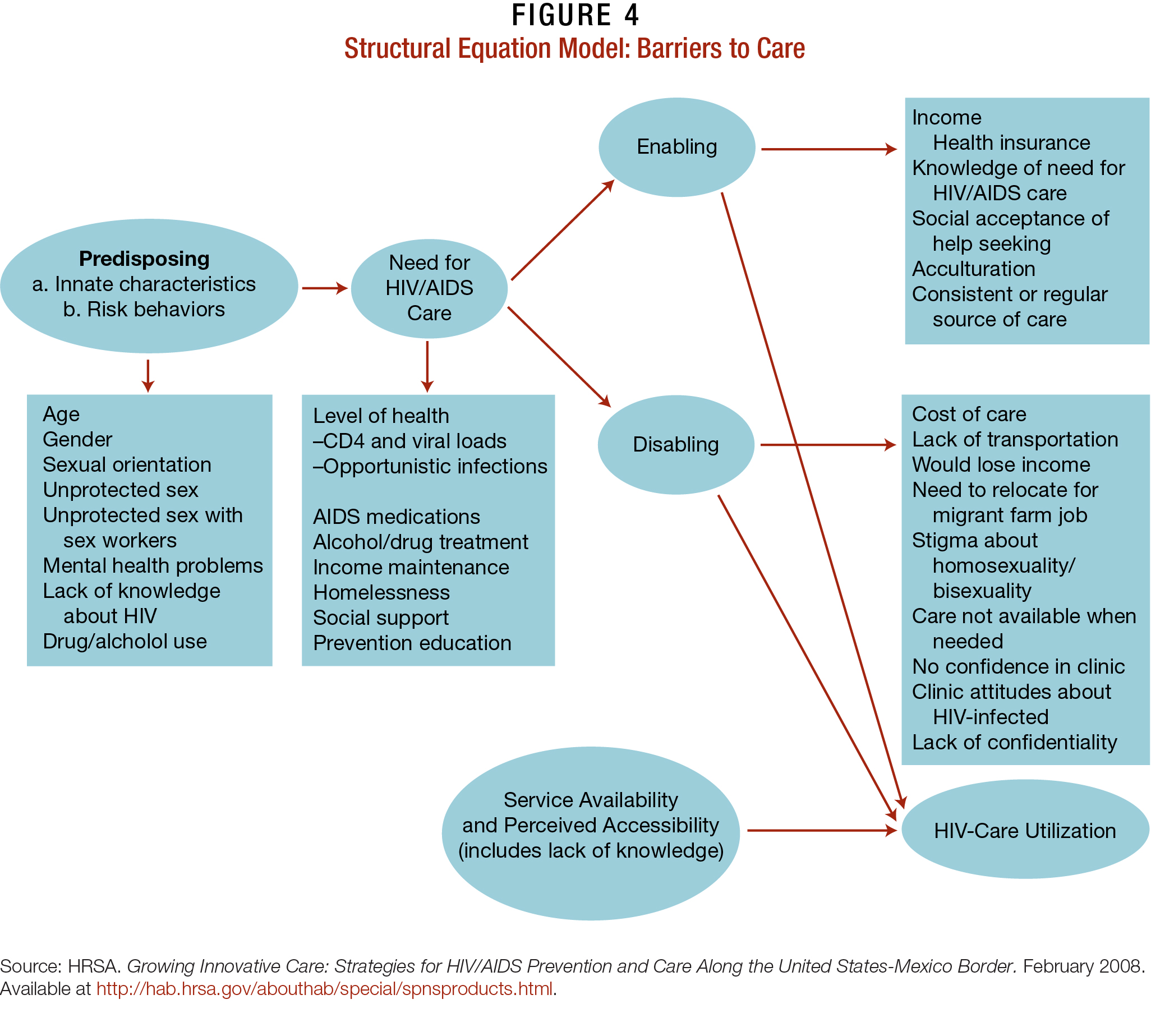

The models in this manual address issues in Figure 4, which demonstrates the iterative path PLWHA commonly take in seeking HIV care. Each PLWHA has their own set of psychosocial and economic issues, as well as personal and cultural factors, detailed in previous chapters of this manual, that dictate their readiness and ability to engage in HIV care.

The models also helped patients overcome “disabling factors” that prevent them from accessing care. Clinics that most successfully engaged hard-to-reach PLWHA developed approaches that expanded upon their current activities, rather than started completely from scratch. Below, the hallmarks of these successful HIV care models are outlined.

Hallmarks of Successful Models of HIV Care

Client-Level Features

- Receive intensive services and support geared to their specific needs. Constant engagement by both clinical and nonclinical staff, particularly within the first few months of diagnosis, and engagement in care are key to positive health outcomes.

- Trust of the medical provider, who assesses client readiness in care and provides health education as necessary.

- Are linked and engaged in care through culturally and linguistically competent mechanisms.

Provider/Clinic and System Features

- Create strong partnerships with other providers.

- Develop and maintain diverse and highly trained culturally and linguistically competent clinicians and staff to meet the needs of vulnerable PLWHA.

- Maintain an accessible, discrete location with nonclinical waiting and office areas, accommodating hours of operations, and flexible scheduling systems to meet the needs of PLWHA.

- Provide active linkages and referrals, where patients are personally guided into systems of care, rather than given a list of names, addresses, and appointment dates. This may include intensive followup to ensure that patients are fully engaged in care.

- Maintain meticulous records and quality improvement standards to ensure that patients receive the best medical and ancillary care services possible. Incorporate modern data software-tracking and information-sharing systems as allowed by their current budget.

- Provide ongoing refresher trainings and put written standard operating procedures, policies, and practices in place to facilitate access to and ongoing engagement in care for PLWHA.

Sources:

- Cabral H, Tobias C, Rajabiun S, et al. Outreach program contacts: do they increase the likelihood of engagement and retention in HIV primary care for hard-to-reach patients? AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S59–67.

- Chart inspired in part by HRSA, HAB. Outreach: engaging people in HIV care. 2005.

Table 1: Definitions of Common Terms and Models of Care

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Adherence to ART | Adherence means taking medication regularly, as prescribed. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence refers to patients who take their HIV medications as instructed nearly 100 percent of the time. Adherence is essential to preventing drug resistance, significantly lowering or achieving undetectable viral loads, and subsequently improving PLWHA health outcomes and reducing transmission risk. |

| Community Viral Load | The average of all viral loads of a specific community of PLWHA results in a measurement called the “community viral load” (CVL). The CVLs of different populations can be compared and disparities identified and addressed. Lowering a community’s CVL requires PLWHA to become engaged in care and ART-adherent, since this means they are likely to have low or undetectable viral loads and less likely to transmit the virus to others. |

| Engagement in Care | Engagement refers to an ongoing series of interactions between PLWHA and a continuum of care with a variety of providers, including outreach workers, case managers, clinic staff, medical personnel, counselors, ancillary service providers, etc. Clinically, patients are considered engaged in care if they have had at least 1 visit in each 6-month period with a single HIV care provider within a 12-month period. |

| Full Engagement in Care | Full engagement in care occurs when PLWHA have a complete, regular, ongoing involvement in primary medical care. Similar to “engagement in care,” it is clinically defined as 2 visits within a 12-month period that are at least 3 months apart. |

| Health Service Navigator | Health Service Navigators (HSNs) are staff members trained to provide intensive case management for PLWHA entering care and/or may be accessing services from partnering providers. HSNs may conduct care assessments and develop action plans to help their clients identify their care goals and understand how they can reach them. |

| Intensive Case Management | Intensive case management involves coordination of medical, mental health, and other services in the context of frequent meetings and check-ins, often for a set period of time. |

| Linkage to Care | Linkage involves the initial connections and entry points of care after HIV testing and disclosure. Linkage may include referral by a case manager to a treatment program for substance use disorders (SUDs) as well as medical and mental health care. In addition, persons who test negative for HIV may be linked to a peer counselor for additional guidance around HIV prevention. |

| Lost to Care | Patients who have had at least 1 visit in the last 2 years with a provider, but have not been to the facility within the last 12 months. |

| Outreach | Outreach is a series of singular events geared to finding people who are at risk for or living with HIV, to offer education and to link people to HIV testing and care. These events can include health fairs and encounters outside entertainment venues. They generally do not refer to ongoing activities that retain people into care, such as appointment reminders. |

| Peer/Near-Peer | Peers and near-peers are outreach workers or counselors who encourage people at risk for HIV to get tested, and work to keep PLWHA engaged in HIV prevention, care, and treatment. Often peers and near-peers are from the same ethnic and racial background and the same general age as the clients they serve. |

| Retention in Care | Describes ongoing, full engagement of PLWHA in care over time. Sometimes used synonymously with “full engagement in care.” |

| Reengagement | Reengagement refers to patients who return to care after having fallen out of care in the past. |

| Sporadic Care | Clinically, sporadic care refers to patients who have seen an HIV provider no more than 1 time in a 12-month period. These patients would be considered unstable in care. |

| Time-Limited | Time-limited interventions take place during a set time period. For instance, a new, reengaging, or unstable patient may receive intensive case management until he/ she is stable and able to better navigate their care independently. |

| Unstable in Care | Patients who are unstable in care—indicated through factors such as missed appointments, not being adherent to ART, and SUDs—are considered at risk and on the verge of falling out of care. |

Table 2: Definitions Models of Care

| Models of Care | Definition |

|---|---|

| Traditional Street/Social Outreach Model | This outreach model often involves having peers engage in outreach with at-risk persons in their communities, often in public arenas, such as public events and entertainment venues. |

| Motivational Interviewing Model | Rather than a singular outreach event, motivational interviewing (MI) is delivered by peers and near-peers, who are trained to provide culturally and linguistically competent counseling. MI is designed to help patients align their behaviors with their treatment goals so they become engaged and retained in care. |

| Health System Navigation/ Retention in Care Coordination | HSNs work with PLWHA clients to support engagement in care with partnering providers. They conduct assessments, codevelop action plans with PLWHA, and coordinate care across providers. |

| HIV Interventions in Jails | This model leverages the jail setting (and related correctional institutions such as parole offices) to identify and engage PLWHA into care. The uniqueness of HIV care in jail settings involves its own model, which in part is a hybrid of several others in this training manual. |

| In-reach (reconnecting past patients lost to care) | Providers work with partnering agencies and use their databases as a resource to identify PLWHA who have fallen out of care, contact them, and help them to reengage in care. |

| Social Marketing Campaigns/ Social Networking Channels | Social marketing uses commercial advertising techniques to “sell” HIV prevention, testing, treatment, and care through messages targeted to specific populations. Television and radio advertisements and promotional materials are often repurposed and circulated online through social networks, such as YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. |

Sources:

- Lounsbury D, Palma A, and Vega V. Simulating the dynamics of engagement and retention to care: a modeling tool for SPNS site intervention planning and evaluation. Presented by HRSA Special Projects of National Significance Multi-Site Evaluation Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine on May 4, 2012, during SPNS Women of Color Initiative Grantee Meeting May 4–5, 2012.

- HRSA, HAB. HAB HIV core clinical performance measures for adult/adolescent clients. July 2008.

- Raja S, McKirnan D, and Glick N. The Treatment Advocacy Program—Sinai: a peer-based HIV prevention intervention for working with African American HIV-infected persons. AIDS Behav. 1007;11(Suppl 5):S127–137.

- Bradford J. The promise of outreach for engaging and retaining out-of-care persons in HIV medical care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S85–91.