SPNS initiatives have tested numerous models of care over the past 20 years. Several of the most successful interventions for engaging hard-to-reach populations are described below.

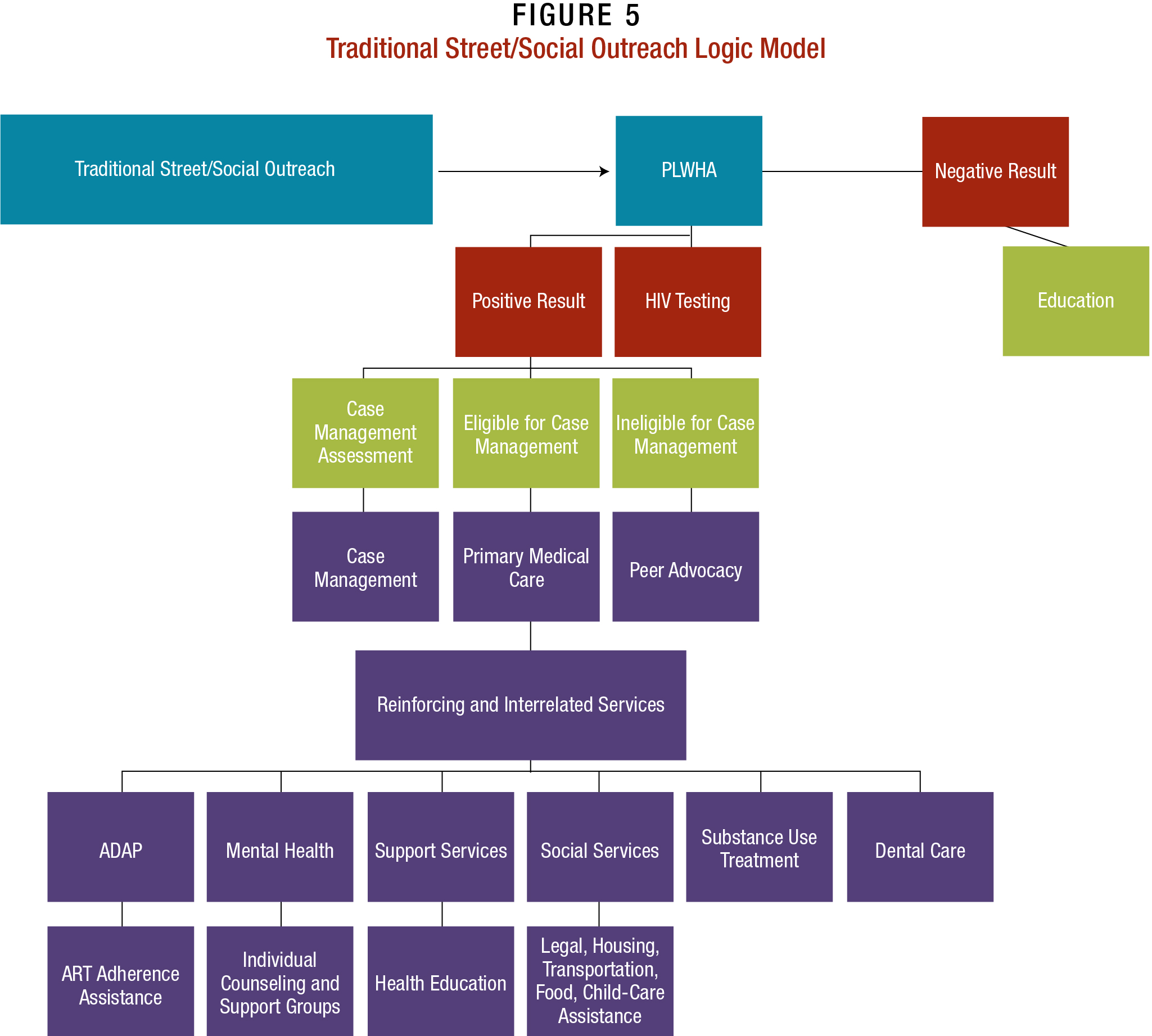

Traditional Street/Social Outreach

Traditional street/social outreach is a common model used to reach vulnerable PLWHA and link them with information about HIV prevention, testing, treatment, and care. In some instances, this may involve providing the actual testing—most often, oral swab testing for immediate results—and hands-on linkages to care. The provider leverages peers and near-peers to approach and work with the targeted population. These are often dedicated volunteers and/or entry-level personnel who are either the same or close in age to the target population and share their ethnic, racial, cultural, and linguistic background. They tend to be able to develop a more immediate rapport with the target population. Most are trained nonclinical staff members and volunteers who may or may not hold other positions within the clinic. Some SPNS providers leverage clients from the target population who had successfully engaged in care through their clinic.48

Outreach workers serve as a link between the community and the clinic, and play an integral role in ensuring that vulnerable PLWHA in those target areas engage in care. The success of this approach rests on the outreach workers themselves. It is critical that they have a caring, nonjudgmental approach and attitude toward potential clients, since many have mental health issues, may be injecting drugs or using other substances, and may be engaged in sex work.

How It Works and Where. Staff are “stationed” in areas and communities frequented by the target population, with outreach workers positioned with a health care van or exhibit booth. Outreach workers also may approach the target population on public transportation or at local service/entertainment venues, including popular nightclubs, bars, and restaurants. These venues and events may be associated with HIV and/or general health, as well as cultural, sexual, and gender identities.49

Encounters with the public may include distribution of condoms and harm-reduction materials (as allowed), and/or educational materials. These encounters are often brief and singular.

Opportunities and Benefits. This approach benefits from its intimacy with—and ready recognition as a medical intervention by—the target populations. The intent of outreach work is to capture the audience’s attention, encourage them to practice safer sex, get tested for HIV, and engage in care as necessary. Since outreach workers usually have time-limited rather than ongoing interactions with people, less training is required for this position than for case managers and health system navigators (HSNs). Outreach workers often offer rapid testing at offsite venues. Those identified as PLWHA are connected directly with a case manager onsite who provides counseling and sometimes chaperones them to another location for followup testing and linkage to HIV/AIDS care.

Resources and Other Logistical Requirements/Limitations. Staff buy-in must be secured through training and, if possible, focus groups. It often proves beneficial to have consumer voices, such as those on the local Ryan White Planning Council, at events as well.

Funding needs for this model can vary, depending on the intensity of the outreach effort. Resources may be needed to train outreach workers, as well as secure necessary solicitation permits. The purchase, rental, licensing, and maintaining of a health van or other vehicle may need to be considered. Educational materials—such as flyers, bleach kits, and condoms—for those contacted through the outreach endeavors may need to be purchased as well.

While this model can be implemented with limited training and in nearly any location, there are some limitations to traditional social/street outreach. Some SPNS sites literally found it difficult to find their target population, although they did take the opportunity to provide HIV and health education to other vulnerable groups. Staff turnover tends to be high since the work is often more seasonal and geared to younger people with limited work experience. Though data collection also can prove difficult outside of an office setting, recent advances in notebook computing, data-tracking software, and Internet connectivity promise to make recordkeeping more streamlined and secure.

Concerns about privacy also make connecting with target populations Challenging. Target populations, such as migrant workers, Hispanics/Latinos, and young men who have sex with men (YMSM) of color, may be reticent about being approached by HIV outreach workers. Pervasive fears of being identified as HIV-positive in their local communities are a concern for these populations.

SPNS sites addressed these concerns by framing their efforts as overall health and wellness outreach, including a menu of free primary care services, such as referrals for mental health care and treatment for SUD/addiction, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and tuberculosis, as well as women’s healthcare services. This approach transforms van-based outreach into a health care resource for the community. Instead of “the AIDS van,” it is a vehicle for providing health care, making it possible for PLWHA seeking care to discreetly approach and ask for assistance without fear of disclosing their status.

This is an idealized vision of the outreach model, and presupposes that PLWHA contacted by outreach workers will follow through and seek care. The one-way arrow in the model indicates the limited depth of the traditional street/social outreach approach. If PLWHA fail to follow through with care, there is a possibility they could be lost to the clinic. Even if they provide a telephone number and/or address, the populations targeted through this model tend to be more mobile, and their contact information may change frequently.

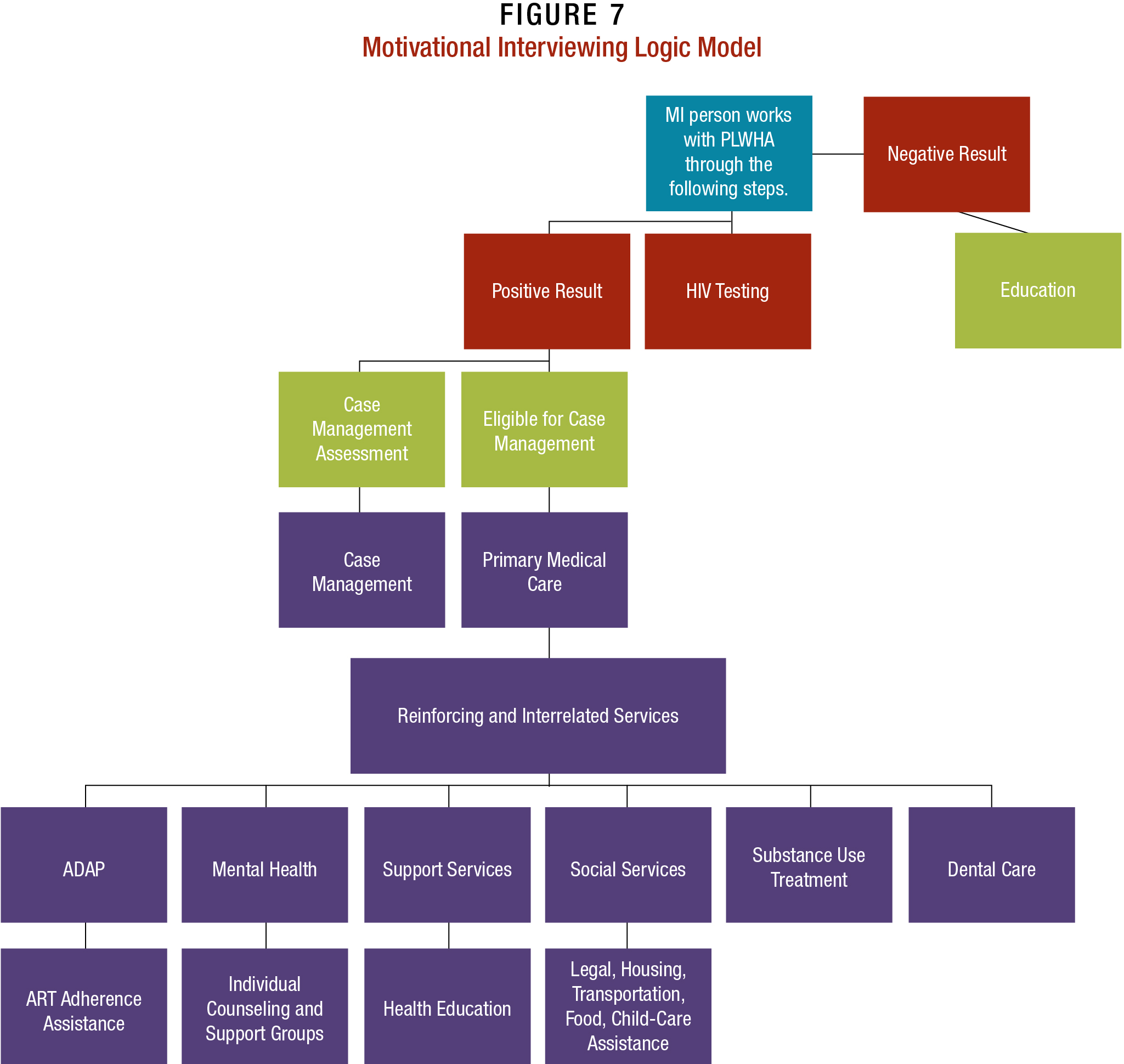

Motivational Interviewing

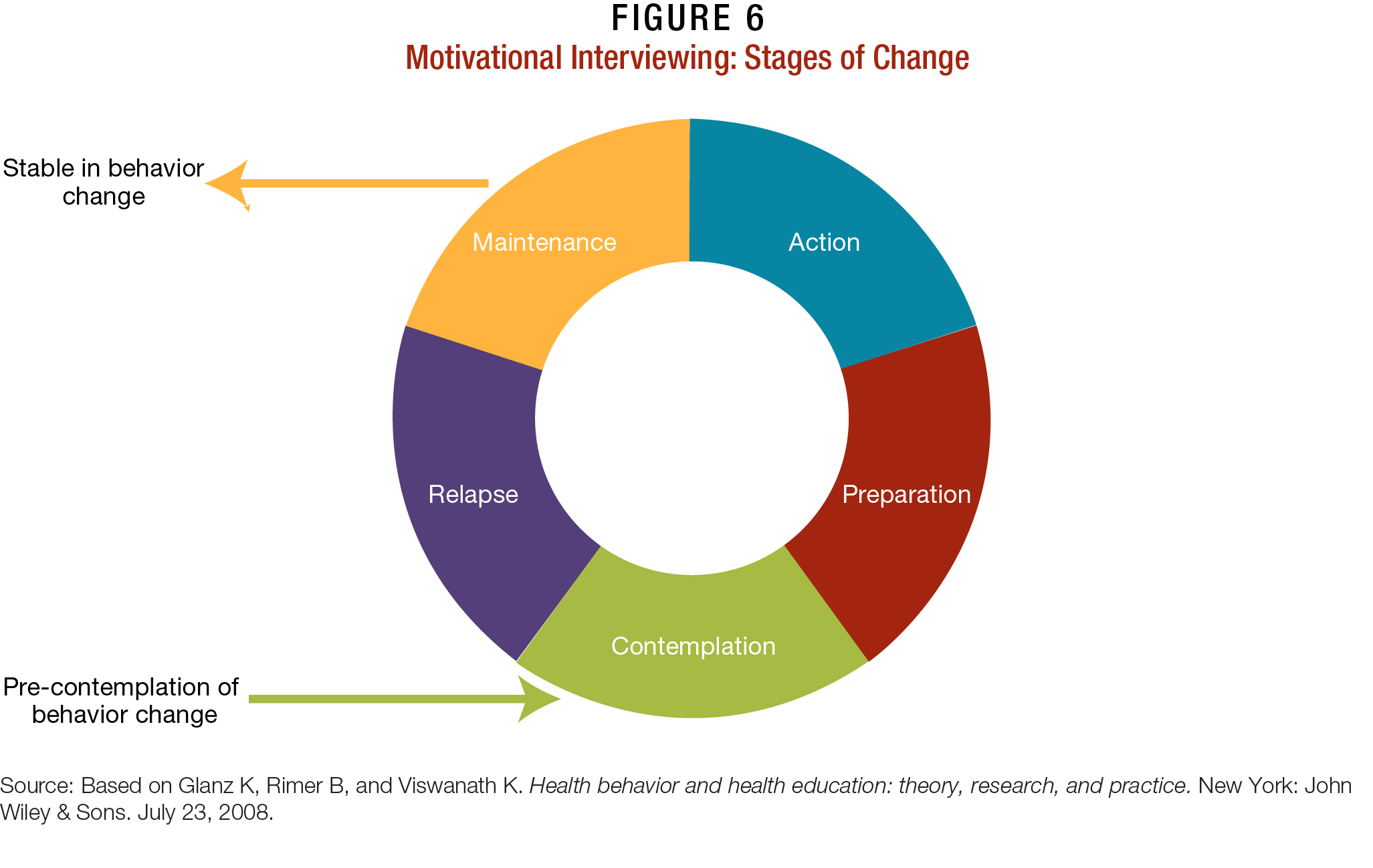

MI is grounded in the transtheoretical model (TTM) of change, and explains or predicts a person’s success or failure in making a proposed behavior change.50,51 In practice, it involves culturally and linguistically competent counseling to create a welcoming environment for PLWHA and encourage them to get tested and engage in care. MI is more flexible than traditional outreach, since it can be provided within a clinic or offsite. When outreach workers encounter PLWHA, they use MI to encourage participants to examine their own motivation to know their HIV status,52 thereby helping them feel more involved in their testing, treatment, and care experiences.53

How it Works and Where. MI generally takes place in a private office, rather than a health van or offsite location. It often requires longer, more intense interaction than other models, since patients are guided through a number of steps geared to helping them identify discrepancies in their health goals and current behaviors, and to devise plans to make positive changes. The stages of change through MI generally involve:

- Precontemplation: This stage occurs at the start of the conversation, when most PLWHA have not yet acknowledged there is a problem behavior that needs to be changed or addressed. For instance, the MI counselor may ask PLWHA if they think they need to address their HIV, and how they might accomplish that under their current circumstances.

- Contemplation: At this stage of interaction, the MI counselor has helped the person acknowledge there is a problem, even if he/she may not be ready or even want to make a change.

- Preparation/Determination: At this point in the conversation, the MI counselor helps the patient get ready to change, often asking more probing questions, such as: “You say you are concerned about your health, but you are not using condoms. Why is that? How does that help you stay healthy?”

- Action/Willpower: At this stage, the MI counselor has helped the person feel empowered to outline and start engaging in changing behavior. This might involve making an appointment for medical care.

- Maintenance or Relapse: MI counselors may check in periodically with PLWHA to see if they have maintained their behavior change and are still in care. Those who were unable to maintain change— as evidenced by falling out of care or returning to past high-risk behaviors—may benefit from intensive case management and participating again in the MI process.54,55

Though time-limited, MI is not a singular encounter, but meant to be part of a relationship that helps PLWHA identify their goals and develop ongoing relationships with clinicians and staff.

MI is often followed up with intensive case engagement such as providing transportation to appointments, and consistent followup via telephone calls, texting, e-mails, and other communications mechanisms. In addition to reminding PLWHA to take their medications and go to appointments, MI personnel discuss the issues their clients may be facing, such as FISI and treatment adherence. When needed, patients are given referrals for additional support services, such as health and medication education resources, nutritional support, housing, mental health, and SUD treatment. In these exchanges, additional incentives or contingencies, such as gift cards and clothing, may be provided to PLWHA to encourage them to remain in care.

Figure 7 is similar to the traditional street/ social outreach approach; however, in the case of MI, the HIV-positive person and MI staff person are engaged in an ongoing dialog. Their relationship, though time-limited (depending on the facility), is far more extensive than that with outreach workers and is meant to ensure that patients reach full engagement in care.

Resources and Logistical Requirements/Limitations. MI requires specialized counselor training,56 and can be an ongoing expenditure for clinics that incorporate MI into their practice. Traditional outreach staff members are sometimes volunteers or employed in a limited fashion. MI personnel often are more permanent staff persons, and are required to undergo extensive training and instruction before being certified to work with clients. Tapes of MI sessions, both practice and real-time, are reviewed by a third party to ensure the integrity of the interviewer’s technique.57 (For more information on MI techniques and approaches, visit the Motivational Interviewing Web site, and also review the resources provided in Section 8, “Continuing the Conversation.”)

To mitigate training costs, several SPNS sites recruited culturally and linguistically competent staff that clients seemed to trust, even if they were not peers. One location reported training a case manager in MI after noting her popularity with their target population. Though much older than the clients, she understood their needs and backgrounds, and the stigma they faced at home and in their communities due to their HIV status and sexual orientation.

The returns on investment are always worthwhile; MI often results in longtime engagement of PLWHA in care, with successful reduction in or achievement of undetectable HIV viral loads. SPNS participants report that PLWHA who became engaged and retained in care through MI often refer their peers to the clinic— an unexpected, though welcomed, spillover effect. This model proved particularly successful in reaching out to younger PLWHA who need support engaging HIV testing and care. The extensive training and sensitivity puts PLWHA at ease. MI requires a quiet meeting space, such as an office or health van, with no one else present. A drawback to MI is that it can be time-consuming, both in terms of execution and training.

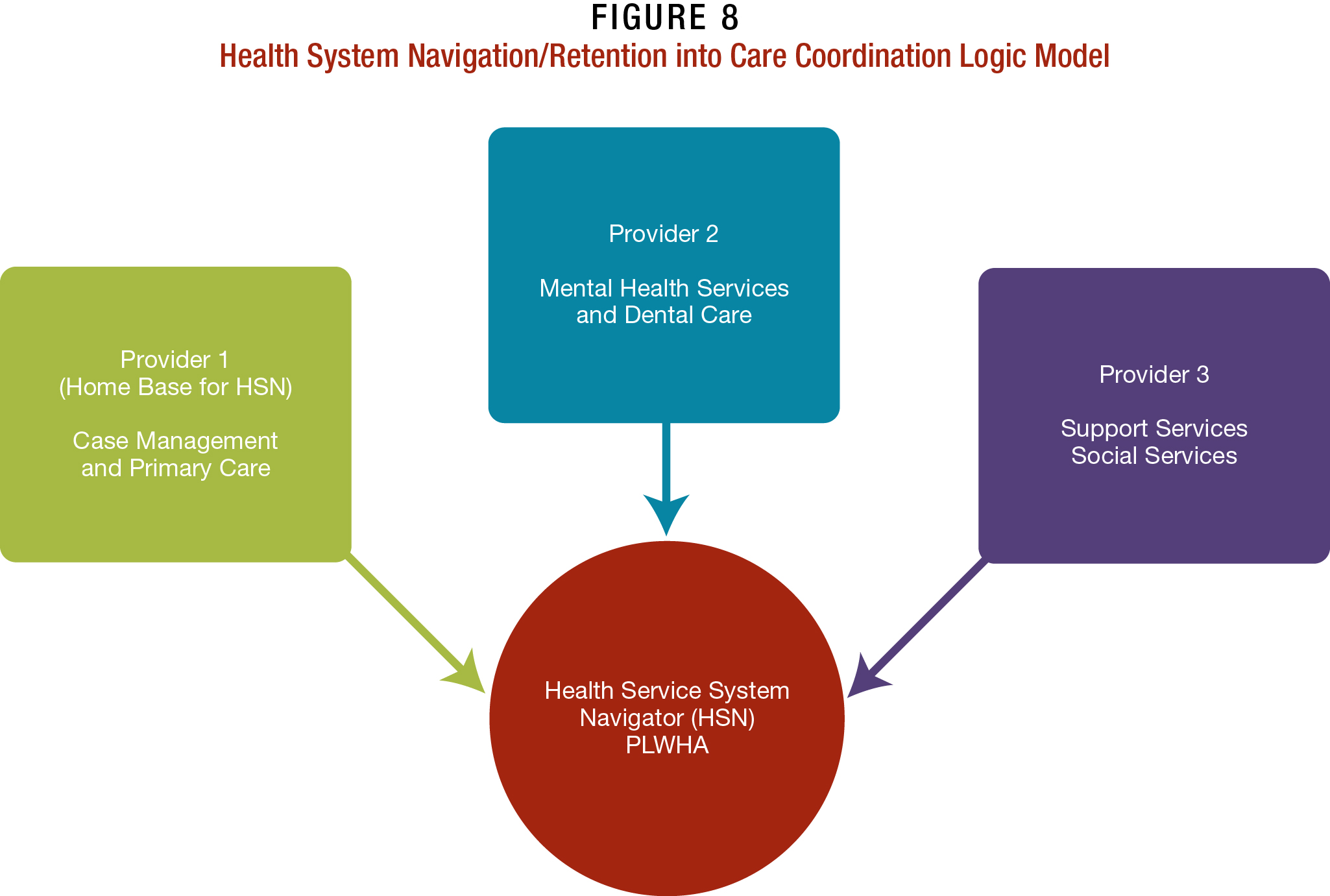

Health System Navigation/Enhanced Case Management

Most clinics are unable to provide all of the primary care and ancillary services that PLWHA need, requiring them to partner with other providers to create a complete spectrum of care. Keeping appointments at different agencies can be overwhelming, particularly for PLWHA who are new to, or reengaging, in care. These patients are often assigned an HSN, a nonclinical staff person whose skill sets combine those of case managers, outreach workers, and/or peer advocates. This service “connector” staff person is sometimes called a service worker or peer advocate.

HSNs offer empathetic and caring support to PLWHA on a personal level. The approach alleviates PLWHA’s fears about linking to and engaging in care, and offers them an opportunity to learn how to navigate services across different providers. They also serve as advocates for clients, acting as a liaison between the patient’s medical providers, case managers, and other clinical staff.

Though similar in some respects to case managers, HSNs are involved with patients on a time-limited basis. Intensive guidance is provided to clients during a concentrated time period to ensure they are fully engaged—and ultimately retained—in care. Patients then take over their own routine of HIV primary care, support and social services, with HSNs following up at regular intervals, often 6 to 18 months later, depending on the needs of their clients and the resources of the partnering agencies.

This personalized or “enhanced” approach to coordinated case management has proven particularly successful with PLWHA who are currently not in care or are unstable in care, and who need extensive support. The model involves several phases:

- The lead clinic/agency partners with one or more agencies to identify and retain PLWHA into care.

- Unstable PLWHA are identified through a variety of means, including interviews and surveys that assess a client’s health literacy and personal situations in relation to FISI, employment, and so on.

- Patients identified as unstable in care are assigned an HSN, who conducts care assessments designed to delineate their care goals and understands how to reach them.

- An HSN helps patients become fully engaged and retained in care, and works to ensure that they keep appointments and fill their prescriptions. This is done through intensive clinic contacts that include, but are not limited to, personal telephone calls regarding upcoming and missed appointments, and chaperoned visits to offsite medical and support service meetings, court dates, health education classes, and so on. HSNs may help PLWHA obtain housing, connect them with medical case management, and provide other services that ensure they stay ART-adherent and retained in care.

- Additional support may be provided to PLWHA who are experiencing challenges with remaining engaged in care. For instance, patients may be offered directly observed therapy, where HSNs and/or other staff help PLWHA take their medications, ensuring ART adherence.

How It Works and Where. The network of partnering providers, in effect, operates like a patient-centered medical home,58 where most, if not all, core medical and ancillary care services are provided under one roof, or in close proximity, ensuring that PLWHA can more readily be engaged fully and retained in care. Clinics that use HSNs to coordinate care have helped to stabilize PLWHA—in terms of their care and their personal lives—and have helped with patient self efficacy. Patients report being able to maintain ART adherence and reaching

undetectable HIV levels. They also are able to manage their SUDs and mental health issues more readily, which are key to remaining engaged in HIV care.59,60 Research has shown that over time, these elements have helped to significantly reduce the community viral load in local areas served by the participating clinics.61

Opportunities and Benefits. HSNs also help case managers from being overwhelmed by their often large caseloads, providing new PLWHA the more personalized care they need to keep appointments and become treatment-adherent.

Resources and Logistical Requirements/Limitations. Clinics must have the staff or the capacity to train current, or recruit new, employees to become HSNs. Some difficulty may come into play if HSNs work across agencies: This can be averted by clear, concise memoranda of understanding (MOUs) and consistent communication among partnering agencies.

This model is relatively inexpensive to implement, although HSNs can suffer from burnout due to the amount of personalized attention involved in supporting and assisting PLWHA. High turnover rates could mean ongoing training costs for agencies constantly hiring new HSNs, as well as inconsistent care for particularly vulnerable PLWHA. Other expenses might be incurred if legal counsel is sought during the creation of formal MOUs. In that instance, agencies may consider informal agreements, in which HSNs would follow their home agency’s protocol around referring clients to other agencies for care.

HIV Interventions in Jails: A Hybrid Approach

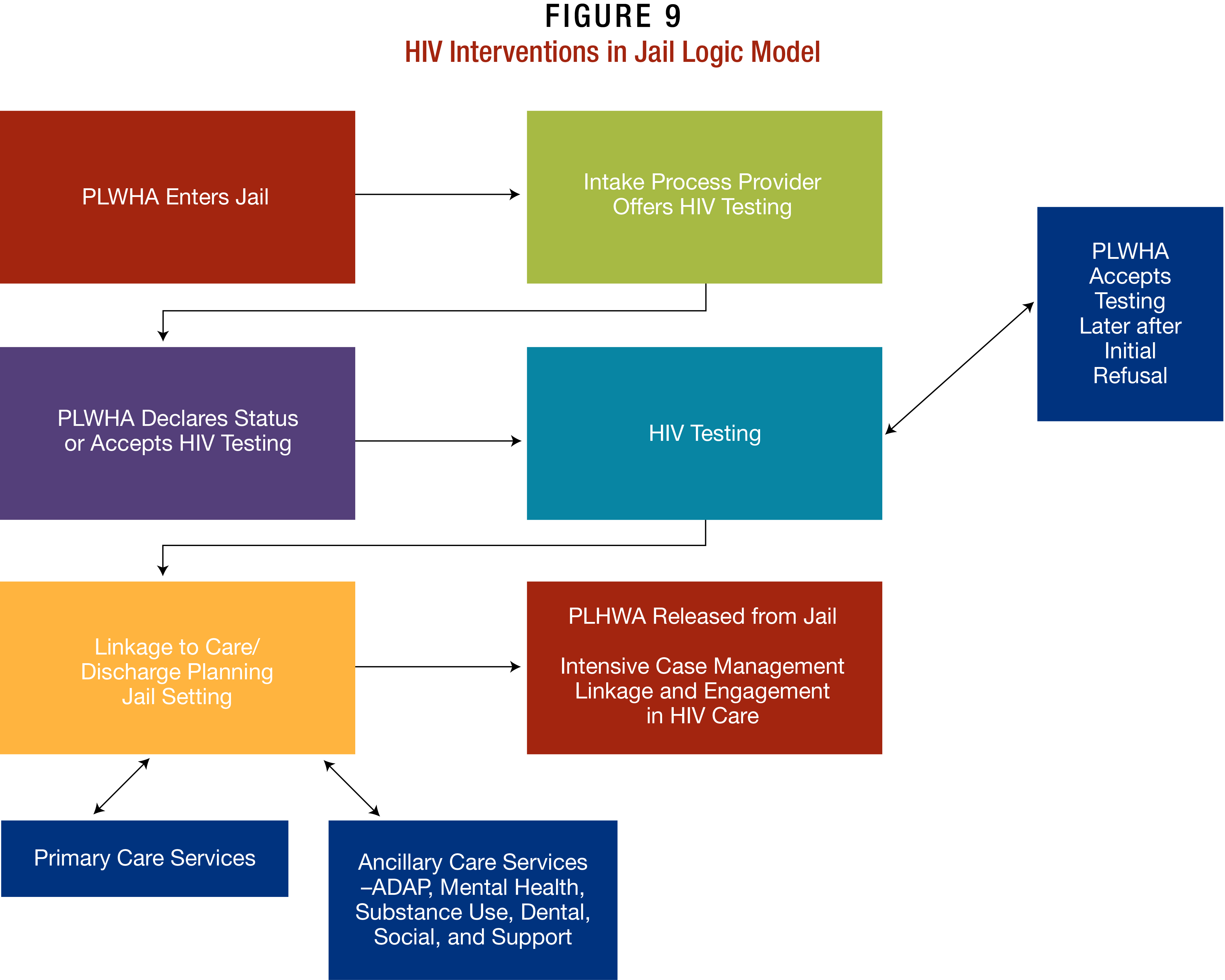

While incarceration can interrupt PLWHA’s HIV care, jail settings also offer an opportunity to identify, engage, and reengage PLWHA in care. Agencies replicating this model, as with the HSN model, are called on to create outside partnerships—this time with their local jails. Partnerships in these instances tend to be controlled by the jails, since they are required to manage the movements and activities of inmates under their supervision— for their protection, and the safety of the staff, visitors, and the general public.

Most SPNS sites working in jails selected the facility closest to their medical offices, since the proximity often encouraged recently released PLWHA to access treatment and care. HIV testing in the jail facility is often offered during the intake process, giving prisoners who opt-in for testing some semblance of privacy in a facility that otherwise is completely open. Some SPNS sites distributed socks and underwear to all prisoners at intake, providing an additional layer of privacy to those who did opt-in for testing since no one was singled out for attention. Others offered testing during group HIV education activities, allowing people who wanted to be tested the anonymity of the group. Indeed, some PLWHA opted to be tested in order to access care, rather than disclose their status to jail staff.

How It Works and Where. Identifying PLWHA as soon as they enter the jail also afforded SPNS site staff the maximum amount of time possible with PLWHA in the facility. Time is often of the essence, since most inmates only stay in jail approximately 24 hours.62 During that time period, SPNS staff maximized their time with patients, conducting health assessments to determine if they required ancillary services beyond primary care, such as those for mental health, SUDs, and FISI.

Several SPNS projects specialized in working with the local courts to create responsible solutions for incarcerated PLWHA. For instance, staff often worked with the courts to have PLWHA with SUDs sent to an inpatient drug rehabilitation clinic upon release. Others were transferred to a monitored halfway house, where they received a supervised introduction to HIV services and care. Perhaps most important, patients often were given transitional care coordination in the form of a “warm exchange” upon release. A care package often containing a letter for their provider that included their HIV test results and other lab work; a packet of appropriate paperwork, such as AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) and/or Medicaid insurance applications; condoms; clothing; food; and a prescription for or supply of their medications.

Opportunities and Benefits. These models did not allow patients to disappear upon release; instead, they were immediately connected with a case manager (sometimes an HSN) who helped them become linked and fully engaged in care. Incentives, such as housing and other specialized services, may be used to entice and stabilize PLWHA released from jails into care.

Resources and Logistical Requirements/Limitations. The greatest challenge to replicating this model is whether a facility can create a partnership with the jail system, which has many competing concerns. Some common issues arose for community health centers and AIDS service organizations when they initiated a relationship with their local jails and began to conduct testing. The issues—and the workarounds SPNS grantees created to address them—include the following:

- Some jail administrators viewed HIV testing as a potential administrative and staffing burden. SPNS sites worked around this issue by outlining exactly what they wanted to accomplish and what staff would be onsite to ensure that everything was completed properly and there would be no additional work to burden jail staff. Sites often sent more than one clinical staff person to the jail to enable multiple tasks to be completed simultaneously, including testing, post-testing counseling (where possible), and health assessments. Finally, staff took the lead in all testing processes, like obtaining medical records for inmates who transfer in from other correctional facilities.

- Some inmates believed that testing is not opt-out due to the coercive nature of corrections. SPNS sites worked around this issue by creating a set script and protocol to help reassure inmates of their rights.

- Staff were not given enough time to test and counsel patients. Jail settings often limit time with inmates, which can make it difficult to get results from even the fastest tests. Clear expectations on both sides about the time needed for and allotted to meetings with patients often mitigated these misunderstandings.

The additional laboratory costs incurred by implementing HIV interventions in jails can often be offset via partnerships with local and State health departments, and through bulk purchasing contracts with vendors. Indeed, flexibility, dedication to safety protocol, and accommodating the partner jail are key to success in replicating this model of care. For instance, some SPNS sites opted to work outside of jails in parole offices to reach recently incarcerated PLWHA, holding general health literacy meetings followed by private appointments for testing and case management. Another site had to refocus their target population when their project, geared to women, attracted only male PLWHA participants.

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A JAIL AND A PRISON?

The terms “jail” and “prison” are often used interchangeably, but there are key distinctions. Prisons are State or Federal facilities that house people who have been convicted of a criminal or civil offense and sentenced to 1 year or more.

Jails, however, are locally operated facilities where inmates are typically sentenced to 1 year or less or are awaiting trial or sentencing following trial.a The average jail stay is 10 to 20 days, according to the United States Department of Justice.

Although jails have average daily populations that are half that of prisons, their populations experience greater turnover. The ratio of jail admissions to prison admissions is more than 16 to 1, and approximately 50 percent of people admitted to jails leave within 48 hours.

Sources:

CDC: What is the difference between jail and prison? 2006.

Cunniff MA. Jail crowding: Understanding jail population dynamics. Washington, DC: National Institute of Corrections; 2002:7.

Reaves B, Perez J. Pretrial release of felony defendants, 1992. National Pretrial Reporting Program. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin. November 1994. NCJ–148818.

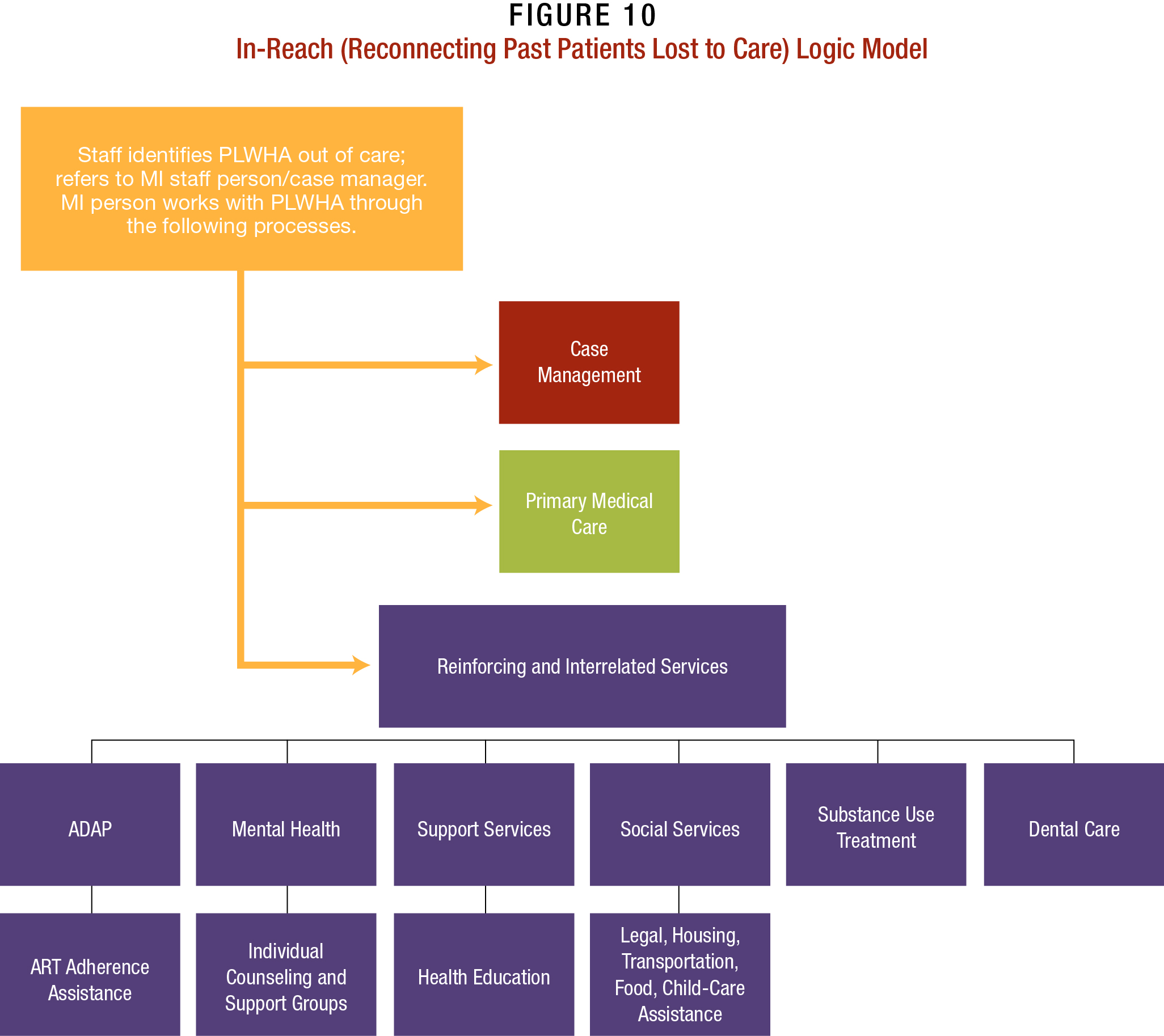

In-reach

Some SPNS sites conducted extensive in-reach efforts within their clinic, as well as local clinics and health departments, to reengage PLWHA lost to care. This approach was most efficient in identifying participants for intervention, particularly with hard-to-reach populations, such as YMSM and women of color. Some grantees coupled this approach with HIV testing efforts in emergency rooms, sexually transmitted disease clinics, health clinics, and other health-care settings these populations often frequent for non-HIV related services.

Special staff training is not required for this model. In general, contact with clients is initiated by a nonclinical staff person who has experience working with the clinic’s database and/or patient records and knows how to quickly identify clients who have fallen out of care. It is recommended that this staff person use a script to help guide their outreach efforts with patients. It is essential that they have a strong understanding of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) rules to ensure that patient confidentiality is maintained, particularly in cases where it is unclear if the contact information on file for a patient is reliable.

How It Works and Where. This process, which involves going through past records and contacting patients who have fallen out of care, requires clinics to have sound recordkeeping practices and reliable information on patients.

Reconnecting with these patients often offers them a lifeline back to care that did not seem to exist for them previously, and shows that someone cares about their well-being. Moreover, it helps lay the foundation for a trusting relationship with the provider and a foundation for care.

Resources and Logistical Requirements/Limitations. People who are recruited back into care often were still experiencing the issues that drove them away in the first place, such as FISI, poverty, under- and unemployment, and lack of insurance. Reengaged PLWHA tended to require (at least initially) intensive case management and/or MI, during which they assessed their health care goals and steps they needed to take to become fully engaged in care. As with the other models, this intensified case management is time-limited, though it often lasted longer than in other models due to the unstable situations of many PLWHA brought back into care.

Other limitations were administrative, such as limited or out-of-date records. Clinics that worked exclusively with paper files experienced major difficulties in finding PLWHA. Providers with modern electronic medical records (EMRs) often had more success with this model.

Social Marketing/Social Networking Campaigns

Social marketing involves leveraging traditional marketing techniques to promote healthy behaviors. In the HIV arena, the approach is often used to encourage people, particularly in high-risk communities, to get tested for HIV, and to engage in treatment and care as necessary. PLWHA and at-risk persons referred to a clinic through these messages not only are linked to HIV care, but also receive additional educational training and resources, and are assigned to a case manager who provides access to ART, mental health care, treatment for SUDs, and other necessary support services.

Social networking refers primarily to online communications through various new media communications tools and information-sharing Web sites, including wikis, blogs, and microblogs. (For more information, visit AIDS.gov’s online tutorial, How to Use New Media.)

Staffing. This generally involves a team of clinical and nonclinical staff creating ideas through focus groups and idea sessions. These staff may also invite clients, members of the public, and consumers on local Ryan White Planning Councils to weigh in on the messaging and images used throughout the development and launch of the project.

How It Works and Where. Social marketing materials are aired on television, the radio, and online; they can effectively target hard-to-reach members of populations with little staff involvement. Some SPNS sites promoted their social marketing campaigns with additional materials such as posters to further raise awareness of HIV and the services they provide.

Many HIV campaigns find additional “legs” through repurposing—reposting information in abbreviated form to encourage audiences to visit the source site—on social networking sites, such as YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. When promoted in this manner, the return on investment can be invaluable, bringing hard-to-reach populations into care—such as youth ages 13 to 29, as well as migrant/mobile, homeless, and IDU populations dependent on intermittent access to mobile technologies for their health information.

Resources and Logistical Requirements/Limitations. Social marketing messaging often requires a great deal of advance planning, design, and focus group testing before launch. Development and implementation can be expensive, since both often involve contracts with vendors for design, film production, and television ad space. Sites considering this approach need to assess how many people they believe will be reached by their products, and if they really believe they can enact behavior change. Moreover, today’s fast-paced media markets can make a social marketing campaign obsolete within just a few months of dissemination.

Users of social marketing techniques have to be prepared for the unexpected, which can speak to misconceptions by a clinic about who is at risk for HIV in their community. For instance, one site created a campaign targeting African American YMSM, who they believed were heavily impacted by HIV in their area. Instead, they primarily received inquiries from Hispanic YMSM, who were not a focus population in their original model. What did they learn? Was that a bad thing? Why did another population respond? Providers may find it helpful to do a test pilot of their social marketing campaign first and then roll it out to broad audiences.

Evaluating the impact of social marketing campaigns can be challenging. It is all but impossible for small clinics to track the populations that have seen their materials and subsequently changed their behavior. The best workaround is to conduct surveys of staff, clients, and the greater community during and after the production process. This feedback should provide some information about who has encountered the campaign, and where they encountered it (such as online, on the street, in the clinic, etc.), their thoughts about its appropriateness and effectiveness, and whether they believe it would generate behavior change among their peers and/or other groups. It also may be helpful to ask what suggestions and comments, if any, the respondent has regarding the social marketing campaign’s taglines, messaging mediums, and materials, as appropriate. (For more information, refer to the Engaging Hard-to-Reach Populations Living with HIV/AIDS into Care Curriculum.)

A note about social networking and models of care: The power of social networking to disseminate HIV information cannot be denied. Online chat rooms are often frequented by MSM and YMSM of color to find partners. Yet initiatives seeking to send out messages to these populations, particularly youth living with and heavily impacted by HIV, have been uneven. Many vulnerable PLWHA, and particularly young PLWHA, have little access to smartphones and other technology due to limited finances.

While most social networking sites are free to use, successful implementation of a Twitter account and a Facebook fan page for a business can be time consuming for staff who need to post and moderate conversations. Some social networking sites require special back-end coding for them to function in a professional work environment. Text messaging is often considered an option as well as to reach PLWHA out of care, but it continues to be extremely expensive.

Online and global positioning system (GPS) chat rooms and social networks have developed dramatically over the past 5 years. One SPNS site was able to leverage these platforms to conduct an online survey of YMSM with the assistance of The George Washington University (GWU) School of Public Health and Health Services’ Youth Evaluation Services (YES) Center. Others used peers to disseminate health messages and invite people to ask health questions in various MSM chat rooms geared to recruiting sexual partners (i.e., online hookups). Unfortunately, many SPNS demonstration sites found social networking sites difficult for outreach purposes. Most users continue to be reluctant to interact with outreach workers in online arenas due to concerns about their privacy.63,64

Some online outreach can create challenges to monitoring staff members’ interactions with patients. This may be especially true when working with outreach workers who are youth themselves. While younger employees may have great facility with the technology and the population with whom they are working, they might require more supervision than other, more experienced personnel.